Written by Isaac Olson

Author’s note: For transparency to readers, this article was slated to be published on May 15th, 2025, and as a result, some information may be out of date. It is important to note that despite the final draft being completed on time, reviewed by the College and University communications teams, and requested for publication by the author and the Currents Board, this article was not granted final publication approval for over 6 months, and only then published because Currents moved to an independent site. The seeming lack of timely communication and administrative hesitation this article received compared to other published Currents content is emblematic of the very issues raised by this article, and underscores the need for members of academic institutions to be more willing to even talk about Palestine.

Just over one year ago, my friend, Ayşenur Ezgi Eygi, was murdered. We must all learn from her martyrdom, especially within the College of the Environment.

Ayşenur and I became friends in the spring of 2024, weeks before we would both graduate from the University of Washington with Bachelor’s degrees. Given the time of year, I wanted to be in a celebratory mood. This was supposed to be the culmination of everything that I had worked for over the past few years, all the hours spent studying for exams and working in the lab. But I couldn’t manage to feel excited about my graduation when 88,000 university students my age in Gaza were unable to even go to school, much less graduate, because of the decimation of every university in Gaza, and the indiscriminate killing of students and academics. By then, around 800,000 youth in Gaza had already been deprived of their education in an instance of “scholasticide,” the systematic destruction of the entire education system and its participants. And when I realized that the 70,000-seat capacity of Husky Stadium could be entirely filled with women and children injured or killed in the genocide Gaza, I felt sick thinking about walking through that stadium for my commencement.

I felt particularly uncomfortable because my country, my city, and my university were profiting off partnerships and investments in companies complicit in facilitating genocide and apartheid. Most notably, these entities all have major ties to Boeing, the largest American supplier of weapons to the Israeli military from 2021-2023. Boeing’s U.S.-made weapons have been used in numerous Israeli human rights violations, making the UW’s commitment to an unconditional relationship with the company abhorrent. In fact, Boeing strategically invests in the UW to facilitate warfare, which has resulted in the UW facilitating warfare through projects like the testing of the B-29 bomber on campus (one of which dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima) and the ongoing development of artificial intelligence for military uses.

The College of the Environment is not innocent. There are examples of Boeing providing research funding for projects in our College that are seemingly used to greenwash its history of pollution. Perhaps even more egregious, the CoE partners with the U.S. Department of Defense, a major supporter of Israel’s genocide and the largest global institutional emitter of greenhouse gases, through the Applied Physics Lab. And yet, even with this complicity staring us in the face, I have seen relatively few individuals within the College of the Environment speak out about the Palestinian Genocide. The College’s apparent silence on genocide is even worse considering that environmental injustice is woven into the fabric of Israel’s occupation.

In Palestine, resistance, resilience, and life are all intertwined with the environment, and nothing makes this connection more clear than olive trees. Not only do olive trees support hundreds of thousands of Palestinians as a critical economic and subsistence resource, but they are an essential part of culture, sovereignty, and life that survive across generations, despite the seemingly harsh environment. Because of this steadfastness, olive trees have become an eternal symbol of Palestinian resilience in the face of oppression.

It is also why Israeli settlers and soldiers so often target olive trees, having uprooted, cut down, or burned nearly 1,000,000 olive trees since 1967. The destruction of olive trees is just one of the many ways that the Israeli occupation has exploited environmental injustice as a weapon.

In fact, the strategy dates back to the early 20th century, when Zionists used environmentalism as a form of “green colonialism,” arguing that Israeli occupiers deserved control of the region because they “made the desert bloom.” Not only does this ignore the centuries of Palestinian caretaking of the environment, but it is undermined by the fact that Israel’s so-called conservation efforts began in the name of covering up the remains of Palestinian communities destroyed in the Nakba, when 700,000 Palestinians were displaced from their homes in 1948.

Additionally, the Israeli government has used water as a weapon against Palestinians for decades. 95% of Palestinians in the West Bank cannot access their traditional water sources due to the Israeli occupation. Because Israel controls all water supply in the West Bank, Israeli settlements are provided with continuous water access, while Palestinians have been deprived of water for up to a month at a time, even amidst drought conditions. Israel also blockades Palestinians from their ancestral homelands, puts Palestinians at disproportionate risk of climate disasters, and seizes or destroys arable Palestinian land, which contributes to 1.3 million Palestinians being deemed food insecure.

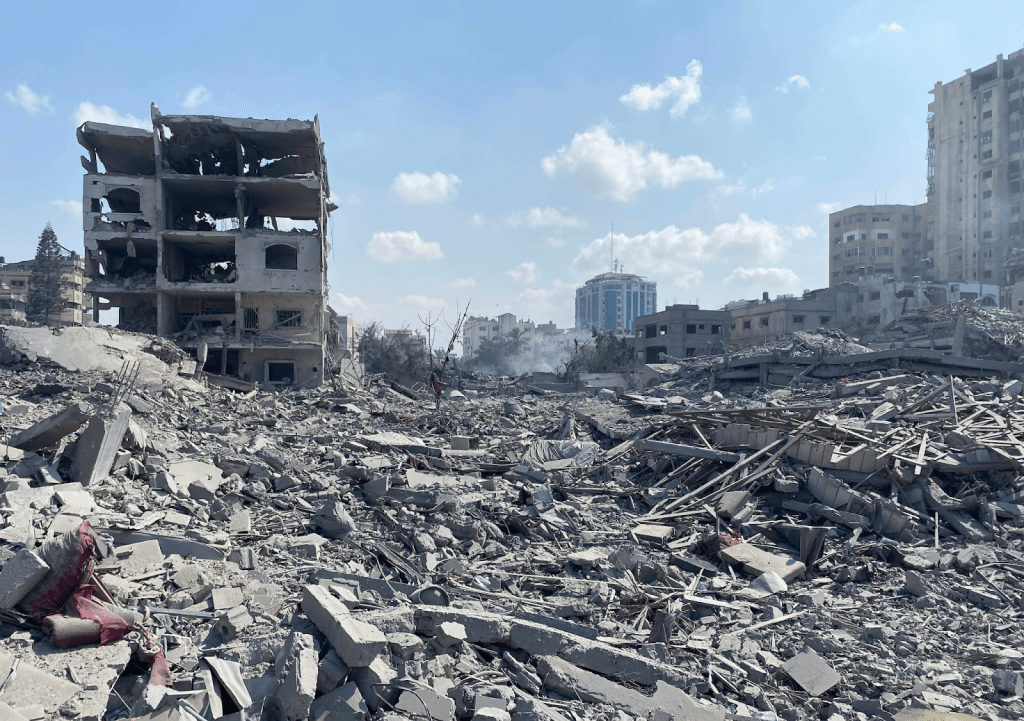

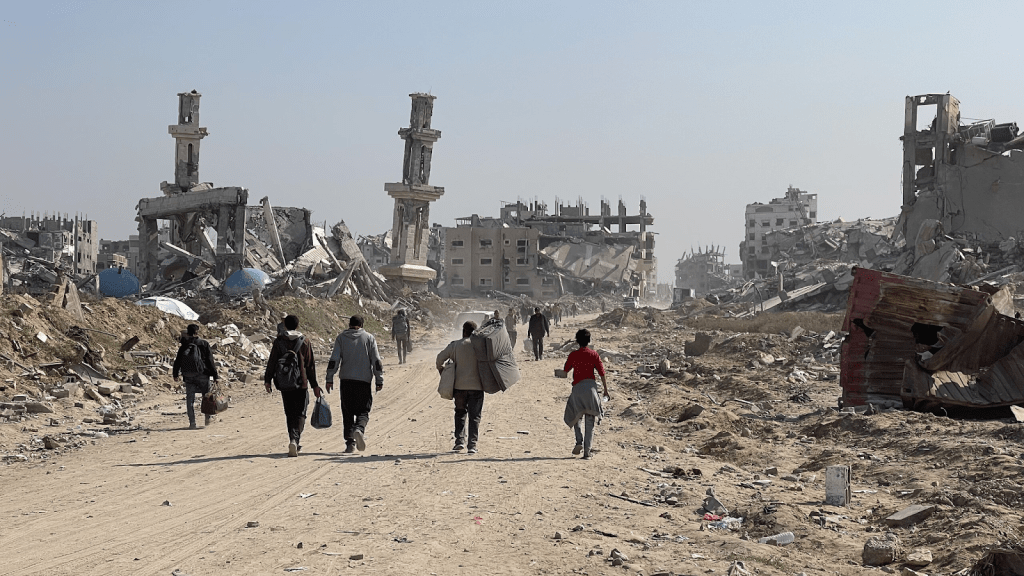

Meanwhile, to facilitate genocide, Israel has routinely weaponized environmental injustice against Gaza over the past 2 years. The United Nations and many human rights organizations have accused the Israeli military of using starvation and water deprivation as weapons of war. The dropping of illegal chemical weapons like white phosphorus, as well as tons of other explosives, has irreparably destroyed the land to the extent that around 70% of both land and buildings have been destroyed. This wholesale destruction has come to be described as an “ecocide,” and the rubble-covered remnants of the destroyed land exemplify the full weight of that term.

The environmental impact of the genocide is not limited to Palestine. On a broader scale, the Israeli invasion has resulted in hundreds of thousands of metric tons of carbon emissions, heavily contributing to the devastating impacts of climate change. Additionally, it must never be forgotten that Israel’s backer, the US military, emits more greenhouse gases than most countries. Failure to speak out in the face of imperialism and genocide is a failure to combat environmental and climate injustice, and as long as this imperialism continues, we are all at risk.

And so, when I saw then-Dean Maya Tolstoy at the CoE’s 2024 Spring Celebration, I took my chance. I asked whether the College had considered putting out a statement condemning the destruction of the Palestinian people and environment, and if/how the College was planning on taking action.

In response, Dean Tolstoy made a remark that, at first, shocked me. She told me that I was the first person to ask her about the College making a statement about Palestine. I could hardly believe it: after eight months of genocide, ecocide, and scholasticide, no one had even asked?

But in retrospect, it made sense. Like previously mentioned, to my knowledge, students, faculty, and administration in the CoE have been largely silent on Palestine. Seemingly, this is because a few factors have made it simpler for the CoE to remain silent. For decades, scientists did not emphasize public-facing communication, even for their research, and communication training remains lackluster. Although scientists are increasingly engaging in outreach, this does not mean that there has been substantive discussion of intersectionality. Many scientists have historically adopted apolitical stances, staying one step removed from political issues, at least professionally. Scientists are often pressured to position themselves as uninvolved in social issues, especially when they are politicized, reinforcing the narrative of the ivory tower of research. This can result in scientists who are entirely ignorant of intersectional social movements, as well as scientists who don’t feel able to comment or incorporate them into their work, even if they recognize intersectionalities. Scientists seem more willing to overcome these hesitations on issues such as public health and climate change, and even social issues like racial and gender equality. But with Palestine, barriers too often result in an avoidance of the significant overlaps between environmental and social justice.

Moreover, discussion of Palestine may be additionally diminished because many members of environmental science fields are uninformed on Palestine as an issue, unwilling to risk funding for their research, unsure of their authority or ability to speak out as (sometimes untenured) state employees, and risk scrutiny and repression if they do speak out. In fact, this trend has been called out across the scientific community, beyond just our College. Given these factors, of course no members of our community had demanded a statement, something difficult to get administratively approved. People were rarely comfortable talking about the subject to each other, including students, faculty, and workers.

But although these factors are an explanation for silence, they are not an excuse. Members of the College must realize that social issues are environmental issues, and so we must be willing to discuss them. This is the foundation of the environmental justice movement. Scientists have increasingly been called to engage in social movements precisely because our work is used to drive change, whether we like it or not. In fact, the College of the Environment claims to actively bridge the intersections between “scientific disciplines, stakeholders and societies, policymakers and the public,” making an outward case for its members to engage in social issues. SMEA’s very existence relies on the recognition and discussion of the intersectional issues impacting both environments and societies. And Palestine must be included as one of the intersectional issues we are willing to confront. This is the message that I wanted the College to promote one year ago, and the lesson that I am still trying to promote now. It is a message that has only gained more importance with time.

As of today, more children have been killed in Gaza than there were students in the UW’s 2024 graduating class, of which I was a part. Imagine an entire class of scholars, the hope for the future, wiped out. Then, remember that the Palestinian people don’t have to imagine this because they are living it.

In the days after my discussion with Dean Tolstoy, I decided against walking at UW’s 2024 Commencement Ceremony, but I did attend in the crowd. I watched as several of my peers held up “Free Palestine” or “Hands Off Rafah” banners as they crossed the stage, including my friend Ayşenur Ezgi Eygi, who was graduating from the Psychology department with a minor in Middle Eastern Language and Culture.

Ayşenur was an inspiring activist who never did half-measures in her work for justice. She was a certified diver who participated in an underwater protest against pollution in the Great Barrier Reef. Understanding the intersection between social justice and environmental justice, she traveled from Seattle in 2016 to participate in the protests against the expansion of the Dakota Access Pipeline through the land of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. And in September of 2024, she traveled to the West Bank as a volunteer to observe the human rights violations ongoing against Palestinian residents due to escalating settler violence. She did this, despite knowing the danger, because she could not fathom inaction or silence in the fact of injustice.

While she was there, she was shot in the head by an Israeli soldier.

Ayşenur was killed on September 6th, 2024. An entire year later, there has still been no independent investigation into her killing.

She has become another martyr, another student killed by Israel, another name that the occupiers would prefer to go unspoken.

Because if we aren’t willing to speak up, Ayşenur and all of the others killed over the decades of the Israeli occupation will fade into forgotten history, and so will the injustices that they fought against.

This is the outcome sought by the Trump Administration, despite its purported focus on opposing anti-semitism. In fact, the president, his administration, and his allies have regularly ignored and facilitated legitimate drivers of anti-semitism, including the rise of white nationalism and online hate speech, while directly worsening Islamophobia. Meanwhile, under the guise of combating anti-semitism, they are waging a thoroughly brutal, demonizing campaign on pro-Palestinian activism, and students and universities have become the prime target. The most vulnerable students, those on visas and green cards, are facing extrajudicial kidnapping and deportation, often for simply standing against genocide. Federal funding for life-saving projects has been illegally frozen unless universities comply with authoritarian attacks, which we are already starting to see at places like UC Berkeley and Columbia University. The underlying terms of the deals are obvious: comply through silence and repression, or fight and risk losing funds. And it is not just university presidents who face the choice of whether to comply or fight. It is a choice that each of us individually must confront when deciding whether to speak out about this repression or not, whether to allow injustices to occur to others in the name of our safety, and, of course, whether to be public in supporting rights for Palestinians facing genocide.

The choice certainly comes with risk. But, really, in the face of genocide and unjust threats of oppression, the decision is easy, and is more important than ever. Silence in the face of injustice is not just, moral, or even neutral: it is complicity. Such compliance will only worsen the dismantling of our entire system of education and the genocide in Palestine, neither of which should be accepted quietly.

I readily acknowledge the hesitancy with which some might approach this, because I started from a very similar spot of focusing primarily on environmental issues and failing to engage as much with the social issues that intersect with them. Even now, I am not perfectly knowledgeable and still make mistakes. But I have only been able to grow because people have been willing to participate in discussion and education, something that will inevitably be lost if we are scared into silence. I believe that no matter how uncomfortable we are with this topic, we must be more willing to engage, to ask questions openly, and seek out resources to edify ourselves.

We cannot be quietly complacent and complicit in the face of ecocide and genocide, especially as those who are willing to speak out are being repressed. We should support more classes explicitly discussing Palestine, host more events uplifting Palestinian perspectives, and establish more partnerships with environmental initiatives in Palestine, such as the Palestine Institute for Biodiversity and Sustainability at Bethlehem University, to the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library. There are so many efforts to uplift, including the instrumental ways that environmental action is supporting Palestine, from the proliferation of Palestinian farmers’ unions as a way of asserting food sovereignty to planting native trees and foods as a form of survival and resistance amidst the genocide.

As a community, we must take initiative to create spaces to engage with Palestine, both in education and action, and once created, the College should uplift these community-driven initiatives. We should be willing to oppose infringements on the rights of those speaking out against injustice. And above all, we must acknowledge the intersection between environmental justice and social justice.

“We must realize that if we believe we must fight to protect future generations from death by climate change, then we also must fight to protect the Palestinian children who are dying every day, and that requires speaking out in the face of repression.”

And like Ayşenur, we must be willing to fight for a future not just for ourselves, but for all.