Written by Kylie West

Like so many other children of the 90s, my dream career as a youth was to become a wildlife biologist. Sometimes, I would sit glued to the television – not for cartoons, but to watch my childhood heroes, Jane Goodall and Steve Irwin, interact with and advocate for the protection of wildlife. Years later, after reaching adulthood and completing an undergraduate degree in the humanities, I couldn’t seem to let go of that dream and decided to return to school. In the wake of Dr. Goodall’s recent passing, I find myself reflecting on my own scientific journey and the ways she inspired me.

When I returned to school at age 30 for a post-baccalaureate degree in Marine Biology at the University of Washington, I experienced a deep sense of fulfillment I hadn’t felt in years. I also, however, quickly became aware that I had held a narrow view of what being a “biologist” entailed. As a deeply sensitive person, it occurred to me that biological research is not inherently gentle and can sometimes be quite invasive and even destructive or inhumane. I have always found myself uncomfortable displacing animals from their environments or disrupting their lives, even in the name of conservation and science. While scientists must intrude on nature for valid reasons, I soon recognized that I was far too sensitive for certain types of research, such as laboratory experiments or working with creatures outside of their natural habitats.

How could I balance my deep empathy for living creatures and my desire to conduct ecological research to help protect wildlife at the species level? Through post-bac research projects, I found the solution: observational work. At Friday Harbor Laboratories, I conducted shipboard research, tallying birds and marine mammals, and analyzed existing datasets to explore patterns in marine mammal density in response to environmental changes. This rewarding research experience deepened my personal values and my interest in marine ecology. A year removed from my research experience at Friday Harbor, I am thrilled to be working on my master’s degree in the School of Marine and Environmental Affairs, where I have begun to scratch the surface of the vast realm of conservation work.

“Through observational research, I found a way to pursue ecological science without compromising my deep empathy for living creatures.”

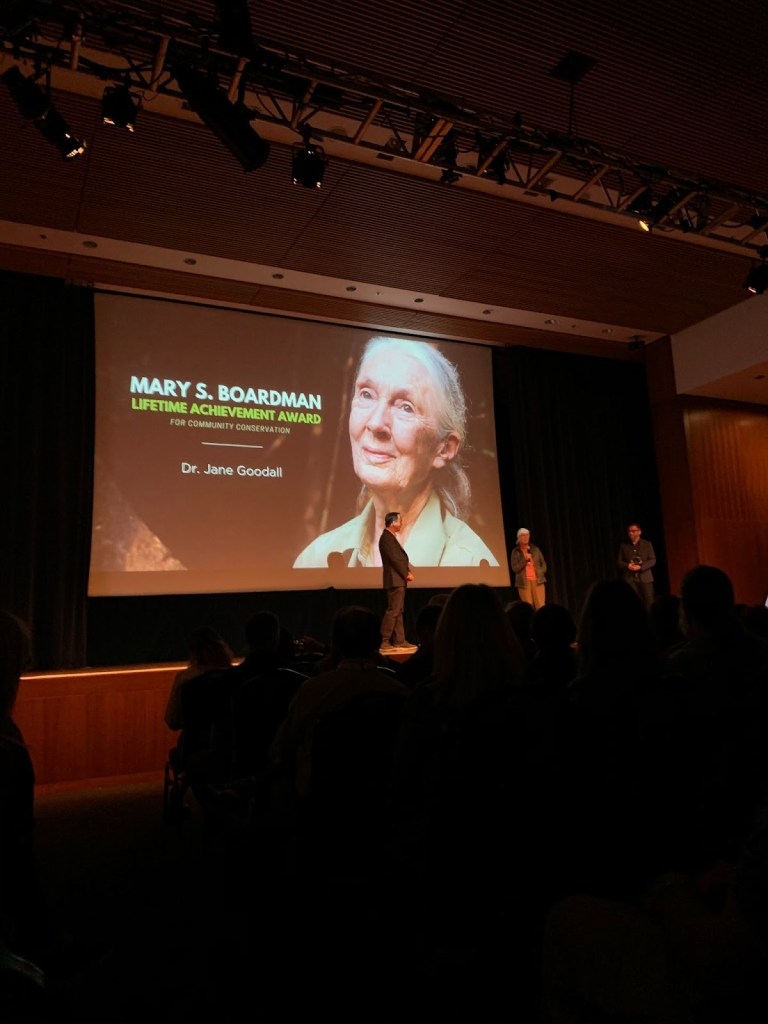

On October 1, 2025, Dr. Jane Goodall passed. Like so many others, I was bereft. A beacon of light in a dark world, she shared her wisdom and hope with people across the globe. Major media outlets (e.g. The New York Times and NPR) published pieces about the conservationist’s legacy, discussing how she revolutionized science, empowered youth, and educated us about wildlife. One of Dr. Goodall’s most salient traits, however, was her gentle spirit. I had the privilege of meeting her twice: initially as an undergraduate at Stanford University, and several years later at the Wildlife Conservation Expo in San Francisco. She exuded a certain warmth and kindliness which, while evident in her documentary films, was all the more noticeable in person. She was a champion not just of science, but also of compassion, and once said, “Researchers find it very necessary to keep blinkers on. They don’t want to admit that the animals they are working with have feelings…. we find that within the lab communities there is a very strong resistance among the researchers to admitting that animals have minds, personalities and feelings.”

If you read any of Dr. Goodall’s eye-opening books on wildlife or watch her documentary films, you’ll learn that she was a master of observation. Her work began in Gombe National Park in Tanzania, where she immersed herself in the culture and lifeways of a local community of chimpanzees. At the outset of her research, she proceeded slowly, as an outsider approaching a new community with placidity, respect, and a kind spirit. Two of her initial discoveries came from patiently observing chimpanzees in their natural habitat: 1) chimpanzees are not vegetarian, as was previously thought, and 2) chimpanzees construct and use tools. These early observations led her to name her chimpanzee friends. She was told not to give the chimpanzees names and instead to assign them numbers and remain objective. Disagreeing with this, Dr. Goodall once said, “We are not the only beings on the planet with personalities, minds, and emotions. And we are part of, and not separate from, the rest of the animal kingdom.”

“We are not the only beings on the planet with personalities, minds, and emotions,” Goodall once said. “And gradually, science came to accept that we are part of, and not separate from, the rest of the animal kingdom.”

Though I focus this article on Jane Goodall, countless others have done critical scientific work through observation. Biologists Rachel Carson and Charles Darwin also made scientific breakthroughs through close observation and spending time in the natural world. Observational traditions existed long before the development of Western science, and Indigenous peoples around the globe have acted as careful observers and protectors of nature for millennia. Grounded in observations and lived experiences of the environment, Indigenous knowledge systems have emerged from sustained relationships with place (Wheeler & Root‐Bernstein, 2020). Rather than positioning humans as detached observers, Indigenous knowledges situate human beings as part of nature, interconnected and interdependent with the wider ecosystem (Tassell-Matamua, 2025).

While observational work has its flaws—particularly the inability to isolate variables or to replicate processes— it can still lead to scientific advancements and enlighten us about wildlife behavior that might otherwise go unseen in more contained or structured experimental studies. There is no single correct approach to science, but it calls for humility and a recognition that we share this planet with sentient, highly intelligent beings who know far more than we may be willing to admit.

Dr. Goodall’s remarkable legacy embodies this philosophy. Her story and values have encouraged me in my own scientific journey, reminding me that I can – and should– maintain my gentle and sensitive spirit as I continue to pursue conservation. She encouraged all of us to follow our dreams, emphasized that even small actions can create meaningful change, and uplifted younger generations as they confront the consequences of past decisions while working towards solutions for the future. People like Dr. Goodall remind us to tread lightly: not only on hikes, or in our shopping habits, or in the carbon footprint we leave, but also in the world of science. As she once said, “Only when our clever brain and our human heart work together in harmony can we achieve our true potential.”

“Only when our clever brain and our human heart work together in harmony can we achieve our true potential.” – Dr. Jane Goodall

References

[1] Tassell-Matamua, N. (2025). Indigenous knowledges. What they are and why they matter. EXPLORE, 21(3), 103144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2025.103144

[2] Wheeler, H. C., & Root‐Bernstein, M. (2020). Informing decision‐making with Indigenous and local knowledge and science. Journal of Applied Ecology, 57(9), 1634–1643. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13734