Written by Madison Gard

What if wastewater wasn’t waste at all? What if it could be used as a resource to simultaneously improve water quality, support climate mitigation, and generate renewable energy feedstocks? By reimagining wastewater in a circular system, phytoremediation by plants–an eco-friendly technique to clean up contaminated soil, water, and air–offers Washington a powerful, nature-based solution to some of its most interconnected environmental challenges.

A System Under Stress: Nutrient Pollution in Puget Sound

Our Puget Sound is one of the most ecologically and culturally significant estuaries in the United States. The estuarine ecosystem supports salmon, shellfish, forage fish, marine mammals, and growing coastal communities. However, the Sound is increasingly stressed by excess nutrients, particularly inorganic nitrogen.

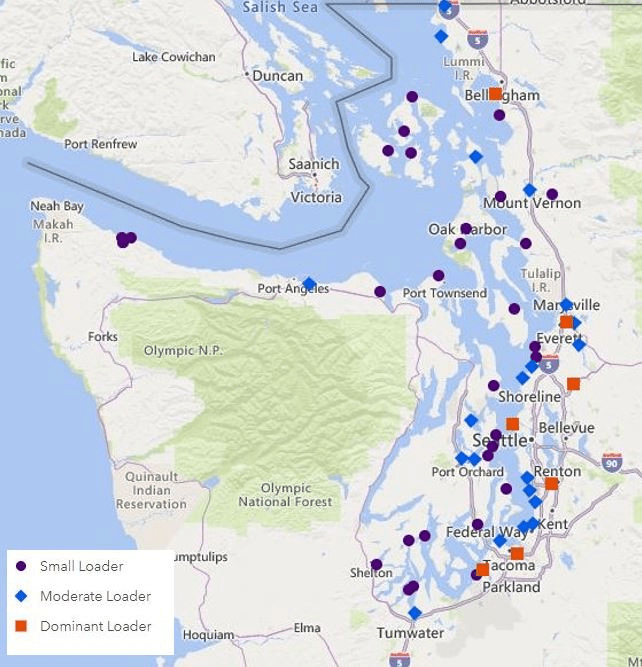

Washington State operates over 300 wastewater treatment plants, with 58 facilities discharging directly into Puget Sound. Collectively, these plants contribute approximately 50–60% of all human-caused nutrient pollution entering the estuary. Wastewater alone accounts for nearly 70% of the human nitrogen load. Due to gaps in their original designs, most conventional wastewater treatment plants were never built to remove nitrogen.

Traditional secondary treatment systems typically remove only 10–30% of incoming nitrogen, releasing effluent with median concentrations around 24 mg/L of dissolved inorganic nitrogen. Even advanced biological or enhanced nutrient removal upgrades—which are costly, energy-intensive, and complex—still struggle to adequately address the cumulative nitrogen burden entering Puget Sound.

The ecological consequences are well documented. Excess nitrogen acts as fertilizer, which feeds algal blooms that eventually die off, consuming oxygen in the decomposition process. The result is hypoxia, or low-oxygen conditions, that can kill fish and other benthic organisms. Decomposition also alters seawater chemistry, contributing to ocean acidification that threatens shell-forming species such as oysters, clams, and crabs. These impacts cascade through the food web, affecting salmon populations and even Southern Resident killer whales already on the brink of extinction.

Nutrient pollution in Puget Sound is more than just a water-quality issue—it is a climate amplifier—weakening ecosystem resilience where it is needed most.

Crucially, nutrient pollution in Puget Sound is more than just a water-quality issue—it is a climate amplifier. Hypoxia, ocean acidification, biodiversity loss, and warming waters reinforce one another, which weakens ecosystem resilience where it is needed most.

The Limits of Linear Infrastructure

Washington’s nutrient challenge is a symptom of the deeper problem in how wastewater is managed. Conventional treatments follow a linear model: remove contaminants to a regulatory threshold, then discharge the effluent to receiving waters. This approach treats nutrients as waste to be minimized rather than materials to be recovered or transformed.

As regulatory pressures under the Clean Water Act increase and climate impacts intensify, wastewater utilities are facing a difficult choice: invest billions of dollars in incremental upgrades that further increase energy use and operational complexity, or reimagine wastewater treatment processes themselves. Linear, energy-intensive infrastructure alone cannot provide the resilient, multifunctional outcomes desperately needed by Washington State. Nature-based solutions such as phytoremediation offer a promising alternative to fill this gap.

Phytoremediation: A Nature-Based Solution

Phytoremediation uses plants and their associated microbial communities to clean pollutants in soil and water. For wastewater treatment applications, phytoremediation can be implemented through constructed wetlands, which are engineered systems that mimic the structure and function of natural wetland ecosystems.

Unlike mechanical or chemical treatment processes, phytoremediation operates through natural biological processes. Plants take up nitrogen and phosphorus directly into their tissues, while root-associated microbes work synergistically with plants to degrade, transform, or stabilize contaminants. Plant vegetation functions to stabilize sediments, slow water movement, and create conditions that enhance nutrient cycling.

Phytoremediation is low-energy, low-maintenance, and cost-effective, offering co-benefits such as habitat creation, biodiversity enhancement, carbon storage, and improved landscape aesthetics.

These living treatment systems are powered by sunlight rather than electricity, and are capable of adapting to variable flows and nutrient loads. Phytoremediation is low-energy, low-maintenance, and cost-effective, offering co-benefits that conventional infrastructure cannot: habitat creation, biodiversity enhancement, carbon storage, and improved landscape aesthetics.

Importantly, phytoremediation has advanced beyond its experimental phases. Decades of research and real-world applications demonstrate that natural and constructed wetlands can remove roughly 50% of total nitrogen from wastewater on average, with some systems achieving groundwater nitrogen reductions of 70% or more. The question is not whether these systems work, but how and where they should be strategically implemented.

The Potential of Constructed Wetlands

One of phytoremediation’s greatest strengths is adaptability. Different wetland designs can be matched to specific treatment goals, land availability, and regulatory contexts. In Washington State, three effective approaches stand out.

Aquatic Plant Systems: Fast, Efficient Nutrient Capture

Aquatic plants that root in the soils of shallow waters, such as duckweed (Lemna spp.), water hyacinth, and water lettuce (Pistieae) are exceptionally efficient at removing nutrients from water. These species grow rapidly, produce high biomass, and are easily harvested which makes them a good match for high nutrient loads and short residence times of cycled wastewater.

Duckweed-based systems are particularly effective for polishing secondary effluent, which consists of wastewater that has already undergone the typical treatments to remove organic matter. Duckweed plants can achieve 60–90% nitrogen removal and 50–80% phosphorus removal while further reducing biochemical oxygen demands. Due to their small footprint and rapid growth rates, these systems can be integrated into existing treatment infrastructure where land availability is limited. Aquatic plants offer a low-energy, nature-based complement to existing conventional treatment processes.

Tree-powered Systems: Converting Wastewater to Biomass

Woody perennial systems—particularly willow and poplar—offer an innovative approach to wastewater treatment by linking nutrient removal directly to biomass production. These fast-growing tree species are well adapted to nutrient-rich effluent and support highly active microbial communities in their root zones, enhancing nitrogen and phosphorus cycling.

Willow-based treatment wetlands can be designed as zero-discharge systems, where wastewater is applied to a contained soil matrix and removed entirely through evapotranspiration, plant uptake, and soil filtration. Evapotranspiration is accomplished by plants transferring water from the earth into the atmosphere when they absorb moisture through their roots and release it through their leaves. Because no effluent leaves the system, nutrient removal can approach 100%, including total nitrogen, ammonium, and phosphorus. In Quebec, willow wetlands have successfully treated approximately 30 million liters of primary wastewater per hectare over three years, demonstrating their capacity to manage large nutrient loads.

Poplar systems operate similarly but are often designed as irrigated plantations receiving treated effluent. In these systems, nutrients are captured and converted into woody biomass, effectively intercepting nitrogen before it reaches ground or surface waters. The resulting biomass can be used for renewable energy or other bio-based products, creating a “wastewater-to-wood” pathway that aligns with Washington’s sustainable forestry goals.

Beyond water quality improvements, woody phytoremediation systems create multifunctional landscapes that store carbon in perennial biomass and soils, enhance biodiversity, and cool surrounding environments. In a warming climate, these co-benefits are essential.

Algal Systems: Tiny Species with HUGE Potential for Biofuels

Algal-based wastewater treatment systems offer one of the fastest biological pathways for nutrient removal. Microalgae consume nitrogen and phosphorus while using sunlight and carbon dioxide to drive photosynthesis, allowing for extremely high nutrient uptake rates relative to surface area.

Algae have demonstrated nitrogen and phosphorus removal efficiencies comparable to advanced treatment processes, while simultaneously producing biomass rich in lipids and carbohydrates. This valuable biomass can be converted into biofuels such as biodiesel, biogas, or bioethanol, creating a direct link between wastewater treatment and renewable energy production.

Nutrients that once fueled harmful blooms in Puget Sound can instead be redirected into controlled biological systems that produce clean water, renewable fuels, and climate benefits.

Algal systems are particularly well suited for integration within existing wastewater infrastructure, where they can treat secondary effluent or capture nutrients upstream of discharge. When paired with carbon dioxide from industrial or wastewater sources, algae experience enhanced growth while contributing to carbon capture. Algal treatment systems exemplify the potential of circular wastewater design. Nutrients that once fueled harmful blooms in Puget Sound can instead be redirected into controlled biological systems that produce clean water, renewable fuels, and climate benefits.

The Role of Biofuels

One of the most compelling advantages of phytoremediation-based wastewater treatment is that it goes beyond removing nutrients to transform them into biomass. This biomass represents a powerful and often overlooked climate opportunity: feedstock resources for advanced biofuels.

Advanced biofuels derived from lignocellulosic biomass, which is the structural material that makes up plant cell walls, are reaching industrial scales. Lignocellulose, composed primarily of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, is the most abundant renewable biological material on Earth. Unlike conventional biofuels made from corn or sugarcane, lignocellulosic biofuels do not compete with food crops and can be produced from a wide range of carbon-based materials.

Environmental liabilities, or “wastes”, can be reimagined as energy assets. Integrated, nature-based systems can power a more sustainable future

Cellulosic bioethanol and biomethanol can be generated from purpose-grown energy crops such as poplars and willows, as well as agricultural residues, forest byproducts, and even municipal organic waste. This flexibility allows biofuel systems to integrate seamlessly with existing waste streams. Environmental liabilities can now be reimagined as energy assets.

From a climate perspective, the benefits are substantial. Life cycle assessments consistently show that greenhouse gas emissions are reduced by an average of 34% for conventional corn-based ethanol compared to gasoline, while cellulosic biofuels reduce emissions by 88–108%, depending on feedstock and production pathways. In some cases, these systems are effectively carbon-neutral or even carbon-negative when perennial plants sequester carbon below ground in roots and soils.

Biofuels offer social and economic benefits alongside emissions reductions. Locally grown plant biomass strengthens rural economies, creates jobs across both high-tech and low-tech sectors, and provides greater control over energy supplies. Because bioenergy crops can be cultivated almost anywhere, they reduce reliance on environmentally damaging fossil fuel extraction while supporting regional resilience.

As Henry Ford, the industrial visionary and founder of Ford Motor Company once observed, “We can get fuel from apples, weeds, sawdust—almost anything.” Today, that vision is more than just speculative. By coupling phytoremediation with advanced biofuel production, Washington State has the opportunity to close the loop between wastewater management, renewable energy, and climate action. These integrated, nature-based systems can power a more sustainable future.

How Plants Can Power Washington’s Bioeconomy with Circular Nutrient Management

Phytoremediation’s climate potential becomes most powerful when wastewater nutrient removal is linked with bioenergy production. Plant biomass generated through constructed wetlands, willow and poplar plantations, or algae cultivation systems offer locally grown feedstocks for advanced biofuels. Depending on feedstock and processing pathways, cellulosic biofuels can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 88–108% compared to gasoline and diesel.

Using wastewater-grown biomass improves these life-cycle outcomes further. Nutrients that would otherwise drive eutrophication are instead captured in plant tissue, while carbon is stored below ground in roots and soils. Local production reduces transportation emissions and supports regional bioeconomies. Phytoremediation can enable Washington to address nutrient pollution, renewable energy, and climate mitigation within a single, integrated framework.

Washington State is at a critical point. Population growth continues to increase wastewater volumes, while climate change intensifies pressures on marine ecosystems. At the same time, Puget Sound has lost an estimated 20–40% of its wetlands over the past two centuries due to development, eliminating much of its natural nutrient-filtering capacity.

Phytoremediation can enable Washington to address nutrient pollution, renewable energy, and climate mitigation within a single, integrated framework.

Conventional wastewater upgrades alone cannot restore these lost ecosystem services. By rebuilding wetland functions within engineered systems for phytoremediation, Washington can invest in infrastructure that works with ecological processes rather than against them. Living systems increase resilience, reduce costs, and multiply benefits. Now is the time to shift from linear waste management to circular designs, from single-purpose facilities to multifunctional landscapes.

For researchers, it offers fertile ground for interdisciplinary collaboration across ecology, engineering, energy systems, and policy. For utilities, it provides scalable options that can reduce long-term costs and regulatory risks. For communities, it creates green spaces that improve quality of life while protecting the ecosystems they love. Some of the most powerful climate solutions are already growing around us. By harnessing plants, microbes, and sunlight, Washington State can transform wastewater from a liability into an asset, one that heals Puget Sound while helping build a low-carbon future.