Written by Hannah Pikel

The Lower Duwamish River Valley has been home to the Dkhw’Duw’Absh people, known today as the Duwamish Tribe, since time immemorial. The river is essential to their way of life, gifting them and other living beings with salmon, shellfish, and water. Colonization of the river valley began in the 1850’s by white European settlers. Longhouses were burned while the river and the land were stolen from the Dkhw’Duw’Absh people. In 1895, the governor of Washington ordered the river to be dredged and reconstructed for ship passage. Colonizers turned the once-winding river unnaturally straight, paving the way for a massive industrial corridor. A shadow of its former self, the river valley now contains a tiny fraction of the natural habitat that salmon and other native species once thrived in [1].

For nearly a century, manufacturers have poured waste rife with toxic pollutants and heavy metals into the river, heavily contaminating the sediments. The Duwamish Tribe and local communities campaigned for years, pushing the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to clean the river. In 2001, the EPA officially designated the lower 5 miles of the river, flowing through neighborhoods like Georgetown and Southpark, as a Superfund Site. The EPA is legally mandated to clean and restore Superfund sites to protect public and environmental health from hazardous waste. The Washington Department of Ecology was also named the primary agency responsible for controlling current and future pollution sources. In an attempt to dissuade the EPA from labelling the river as a Superfund site —and to avoid the cost of clean-up and bureaucracy— the City of Seattle, King County, the Port of Seattle, and Boeing formed the Lower Duwamish Waterway Group [1]. The group offered to clean the river on their own terms but were unsuccessful in their attempt. All of the group’s members were eventually identified by the EPA as partially liable for the river’s cleanup and restoration. Large scale dredging of the upper river to remove soil-bound pollutants began in November 2024 and is now 50% complete. The cleanup will work its way downstream and is projected to be completed in 10 years.

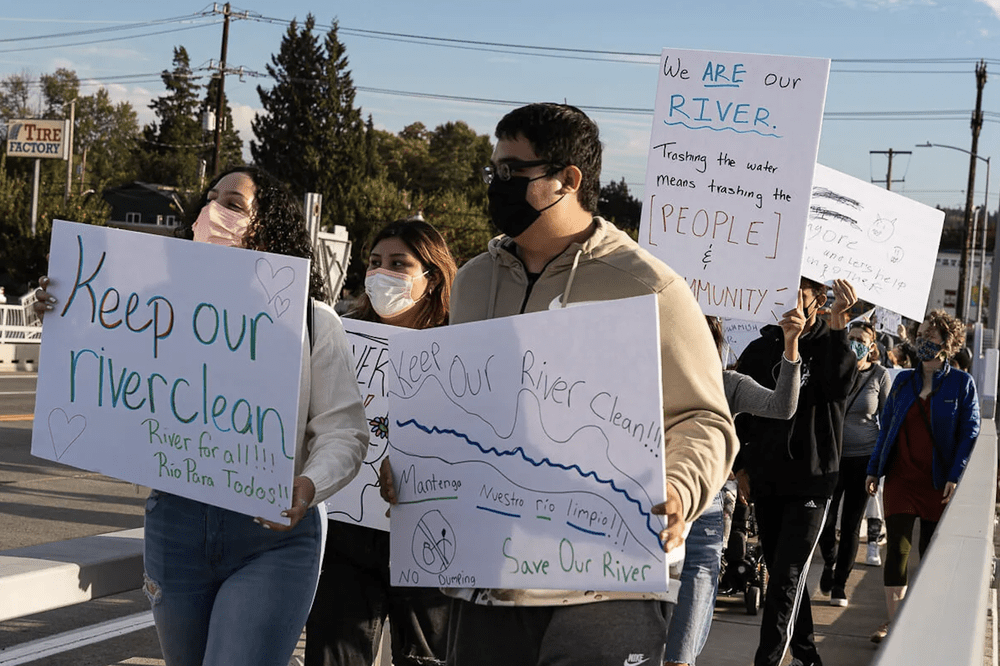

The burden of the river’s pollution falls on surrounding communities like the Duwamish Tribe and residents of South Park and Georgetown. The residents of these neighborhoods, who are mostly low-income people of color, face higher rates of pollution and negative health outcomes than other areas of Seattle. Restoration of the river is inextricably tied to environmental justice for the people who call it home. After decades of inequitable conditions, community members formed coalitions to strengthen their collective power and capacity for self-advocacy. These community coalitions play an important role in restoring the Lower Duwamish River Valley ranging from implementing and stewarding projects to acting as community watchdogs and advocates.

After the EPA’s Superfund designation, community members and the Duwamish Tribe founded the The Duwamish River Community Coalition (DRCC) to serve as the Community Advisory Group to the EPA’s efforts. The coalition began as the Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition, but rebranded in 2021 to reflect shifting priorities in the community such as health concerns and climate justice. The DRCC often collaborates with non-profit organizations, other community coalitions, and the Duwamish Tribe to advocate for and monitor the river’s clean-up.

Duwamish Alive, another community coalition, works to restore native habitat and spread awareness of environmental issues in the river valley. This group collaborates with tribes, businesses, non-profits, and other coalitions like the DRCC. Established in 2006, Duwamish Alive is now composed of many community associations that pool resources such as tools, knowledge, and volunteers. They host volunteer events throughout the year to coordinate invasive plant pulling, trash pick up, and planting native species.

Community coalitions like the DRCC are the voice of community’s wants and needs in restoring the river. In 2009, the DRCC facilitated the Duwamish Valley Vision Plan. They collaborated with the community through workshops and interviews to create a map of what the community wished the valley looked like. The vision report included a desire for job growth through restoration work and increasing eco-tourism, becoming stewards to restoration sites that promote wildlife, and restoring ecosystem services to mitigate pollution. Community involvement events like these inform the DRCC’s advocacy in policy making spaces. The DRCC uses public commentary and their role as an advisory group to the EPA to incorporate the community’s voice into the restoration process.

With many restoration projects facing funding constraints, community coalitions increase project feasibility by facilitating volunteer work. Both the DRCC and Duwamish Alive recruit volunteers through community programs and events. For example, the DRCC Youth Corps Program teaches teens about environmental justice and helps build and maintain restoration projects. Duwamish Alive holds regular events for volunteers to conduct site maintenance. This network of volunteers is achieved through close collaboration with other groups, social media, and community outreach.

Community coalitions have played key roles in the formation and maintenance of important restoration sites. The DRCC is deeply involved in lobbying the local government for restoration and cleanup. In 2007, they pushed the City of Seattle to create a park at Terminal 117, an old port terminal identified as a separate Superfund site in 2003. After the site was cleaned of contaminants, work began to establish a park with public water access and restored salmon habitat. The park is now completed and renamed the Duwamish River People’s Park. Beyond the initial restoration of a site, there is still much work to be done. Without stewardship, restoration sites can regress or continue to be degraded [2]. The volunteers coordinated by both the DRCC and Duwamish Alive serve as stewards to restoration sites through regular vegetation maintenance and trash pick up.

Community coalitions can serve as watchdogs and advocates for project effectiveness. Historically, the government agencies and companies mandated to restore the Duwamish have prioritized cutting costs over project success and effectiveness.When dredging to remove polluted sediment began on the river, a member of the community and DRCC collaborator —local legend John Beal— noted the wildly ineffective dredging buckets that spilled contaminants back into the water [1]. The DRCC and others successfully pushed the city to comply with proper dredging methods. Similarly, during the cleanup of Terminal 117, the DRCC discovered and called out the EPA’s lackadaisical attempts to test and remove polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). After advocating for further testing and removal, the EPA eventually returned to better clean the site [1].Without community coalition involvement, restoration projects like these would have been ineffective and pollutants would continue to harm environmental and human health.

When asked about the challenges community coalitions face, DRCC Operations and Office Coordinator Khalia Tenari stated that, “the DRCC operates at the intersection of environmental justice, cleanup policy, community needs, and restoration outcomes, which presents several challenges. Challenges include limited restoration capacity, negotiating technical regulatory systems, funding constraints, and balancing community justice priorities with long-term cleanup and habitat goals.”

The approach of restoration work matters when the community is facing environmental justice and health concerns. In 2019, University of Washington researchers wanted to construct a floating wetland in the Duwamish river. Both the DRCC and Duwamish tribe voiced concern that the project would not serve as an effective salmon habitat or be beneficial for the community. Despite their vocality and knowledge of the river, they were ignored in both the research and permit approval process [3]. This is only one example of the decades of disregard for community voices by outside organizations and high level decision makers.

Ecological restoration goes beyond a single project or site; successful restoration requires sustainability through stewardship and support from local communities

Involving community coalitions and the people they represent can have significant effects on the success, connectivity, and long-term sustainability of habitat restoration. Other restoration projects have cited community involvement and support as a major component of project success [2, 4]. Ecological restoration goes beyond a single project or site; successful restoration requires sustainability through stewardship and support from local communities.

The communities in the Lower Duwamish River Valley carry the burden of pollution and habitat destruction. Rampant industrialization over the past century has diminished tribal and local access to the river and led to negative public health outcomes. The community’s wants and needs have been systematically ignored by the city, federal government, industry, and researchers throughout the restoration process. Coalitions funnel community passion and dedication into a powerful force of advocacy, creating more successful restoration outcomes. Researchers and policymakers alike must prioritize them in the restoration process. As researchers, we should be seeking out coalition input as active participants in restoration research, project design, and implementation. Not only will this improve project success, but it will create better, longer-lasting restoration outcomes for human, community, and ecological health.

References

[1] Cummings, B. J. (2020). The River That Made Seattle: A Human and Natural History of the Duwamish (1st ed.). University of Washington Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780295747446

[2] Shackleford, N, Hobbs, R, et al (2013) “Primed for change: Developing Ecological Restoration for the 21st Century” Restoration Ecology, 21(3): 297-304.

[3] Klein, S., Lee, J.S., Courtney, S., et al (2022). Transforming Restoration Science: Multiple Knowledges and Community Research Cogeneration in the Klamath and Duwamish Rivers. The American Naturalist, 200(1), 156-167. https://doi.org/10.1086/720153

[4] Higgs, E (2005) “The two-culture problem: Ecological restoration and the integration of knowledge”. Restoration Ecology, 13(1):159-164. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/doi/full/10.1111/rec.12012